What is a Consent Decree?

Under the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, Congress gave the Department of Justice (DOJ) the authority to file civil actions in federal court whenever it has reasonable cause to believe that a local law enforcement agency has a “pattern or practice” of unconstitutional policing. Since the inception of this law, the DOJ has avoided litigation to provide proof of negligence but instead has solely conducted its own investigations to do so. If the DOJ finds evidence that proves the department has a problem, it will begin the process of initiating a consent decree, which is a legally binding agreement between a city or county and the DOJ with the intention of eliminating a pattern or practice of unconstitutional policing.

CONSENT DECREES

COST CITIES $10 MILLION

A YEAR ON AVERAGE

THE CITY OF CHICAGO HAS

SPENT NEARLY $900 MILLION

IN THE FIRST SIX YEARS

Who is in Charge?

All consent decrees require the city to hire a monitor to oversee compliance with the requirements in the decree. The monitors must be approved by the DOJ and a federal judge and are paid for by local taxpayers. The costly consent decree monitoring system lacks transparency, provides disincentives for compliance and has proven to be ineffective. The for-profit monitoring system has corrupted the reform process, creating a need to reform the reformers.

How Are Consent Decrees Evaluated?

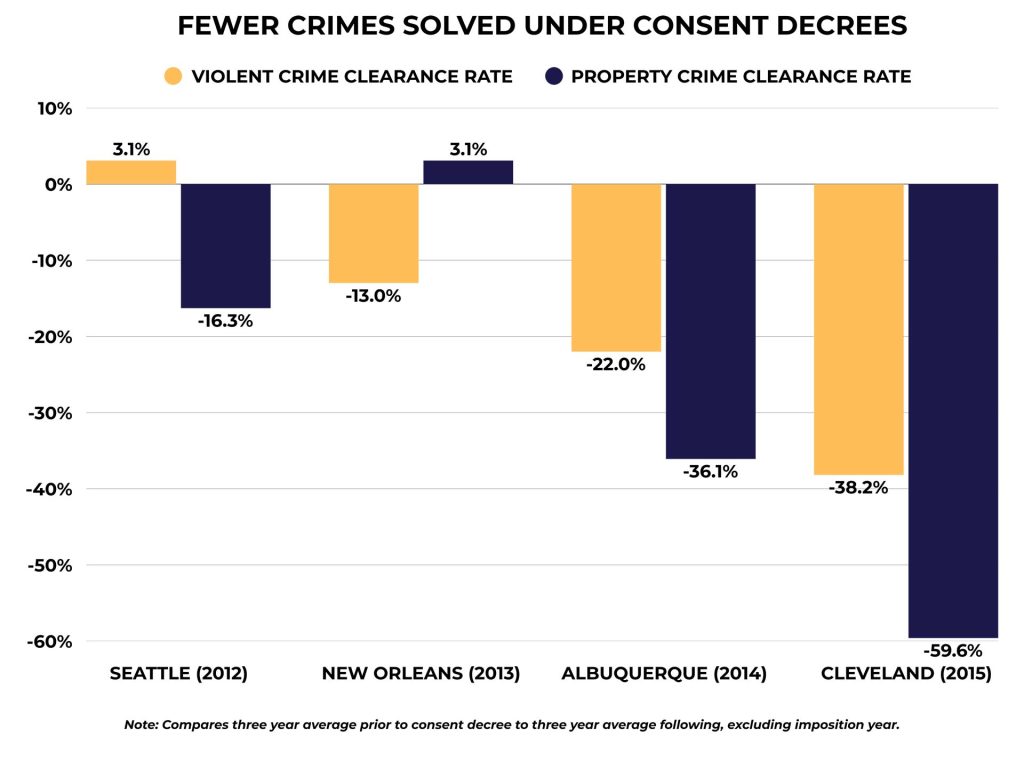

The purpose of a consent decree is to eliminate a pattern or practice of unconstitutional policing. However, “success” is measured by a department’s execution of the terms of the consent decree — not by outcomes or results. The system is designed to check boxes on the consent decree to the satisfaction of the monitor, DOJ attorneys, and the federal judge. The success of a costly government program should not be measured purely by compliance, but rather by the impacts on the communities these programs aim to serve and the constitutional rights they are supposed to be protecting.

Even though consent decrees have been used for more than 30 years, a thorough evaluation of their effectiveness has never been performed.

MOST CONSENT DECREES LAST MORE THAN 10 YEARS

MONITORS MAKE BETWEEN $500,000 AND $4 MILLION A YEAR. They decide when the consent decree ends — if ever.

Key Concerns With Consent Decrees

Expensive & Burdensome

Consent decrees are the most burdensome and expensive reform model there is. The incredibly high costs ($10 million a year or more) of consent decrees (due to the costs of monitors, trainings, technology, reporting, and more) take away from resources that could be used to better the communities these jurisdictions serve.

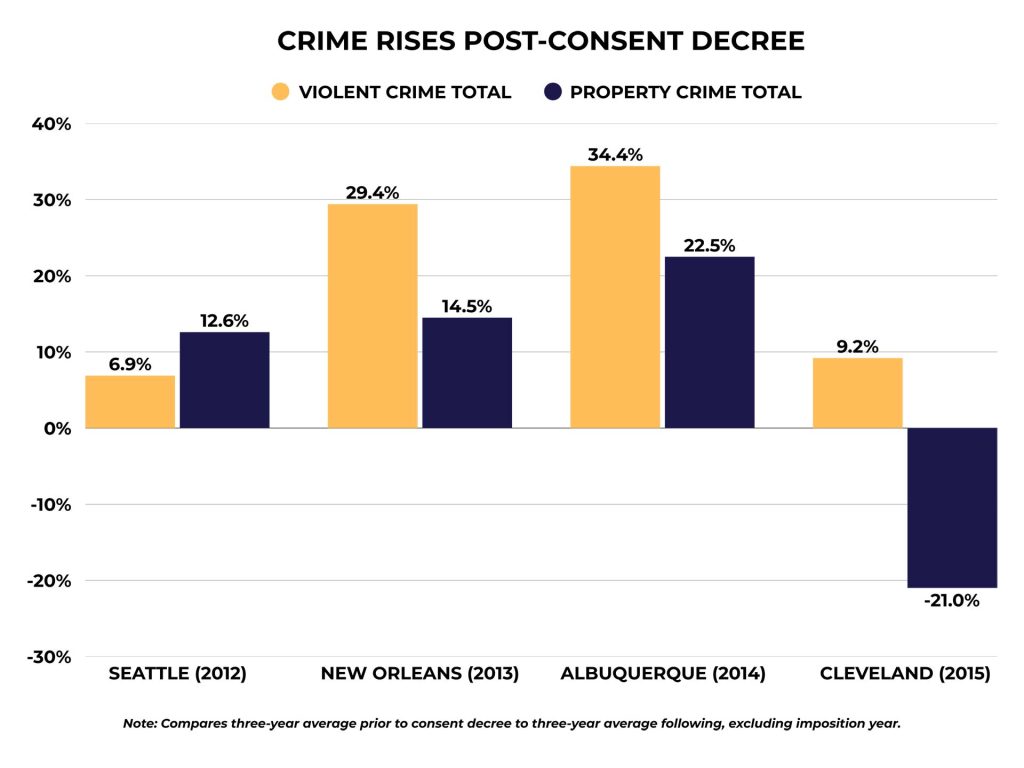

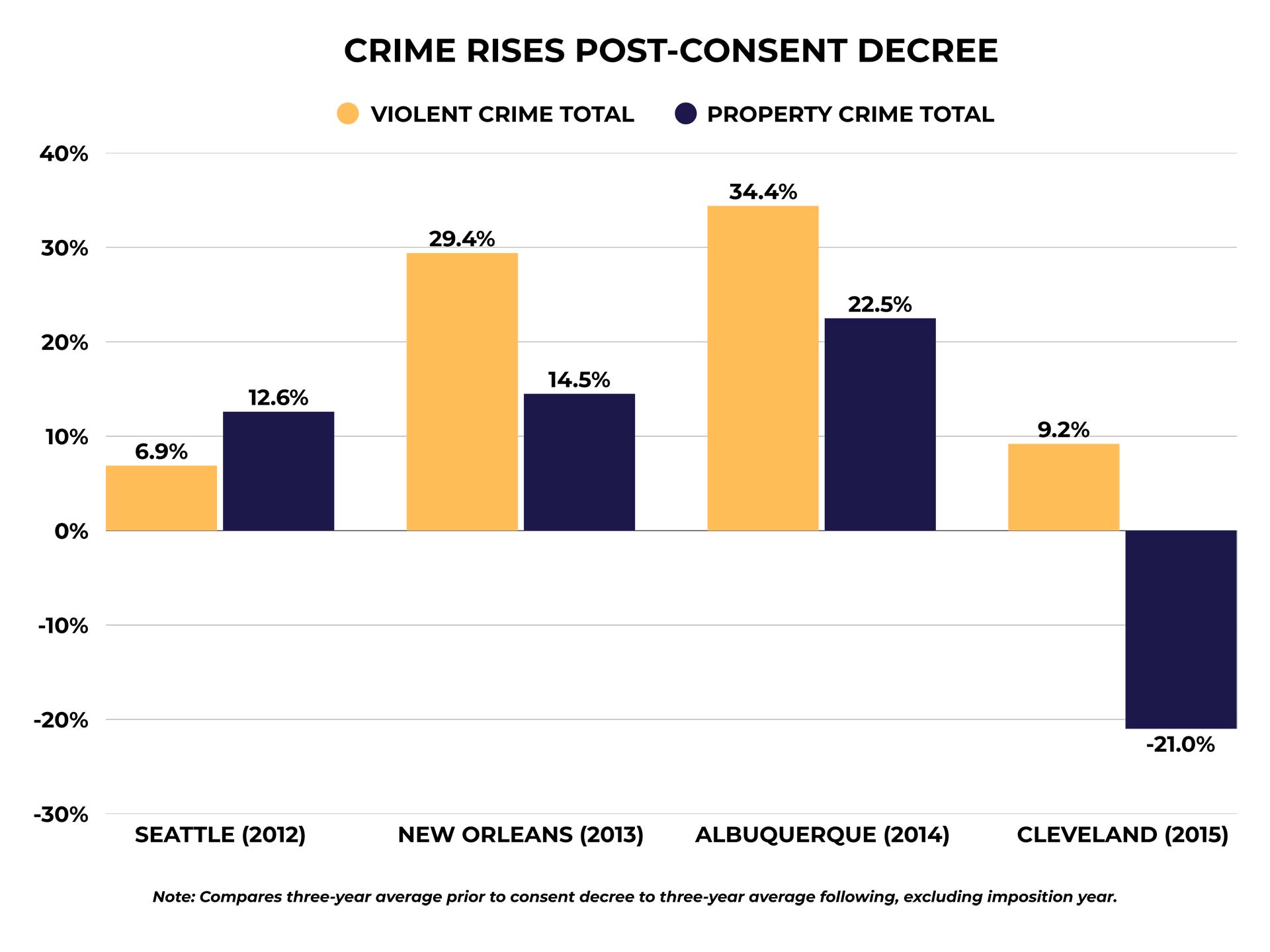

Sharp Increase in Violent Crime

Many communities with their police departments under consent decrees saw violent crime rates skyrocket immediately after their consent decrees took effect. This is due to suppression of proactive policing by consent decree mandates for reduced stops, arrests, searches, and uses of force.

Impacts to Officer Retention

Consent decrees are incredibly invasive to an organization and the way the organization functions — creating friction that may push some officers to leave the department. As a result of this, there is evidence that suggests that under a consent decree police departments relax their typical standards for recruitment to get more officers through an academy.

Missing Evidence

There is no evidence to support the notion that satisfying the terms of the settlement effectively leads to more equitable policing.

Due Process

Consent decrees are often created by the DOJ in response to the actions of just a few officers in a department — without the DOJ needing to prove that the officers’ misconduct was caused by poor policies and/or training. Instead of holding individual officers accountable for their misconduct, the consent decree punishes the entire department and all its officers. This reduces morale and leads to de-policing, disengagement, and resentment toward their department and leadership.

Transparency

Consent decrees have no transparency, and the reform process is conducted behind closed doors with little, if any, community involvement. Often the public is locked out of the process — including monitor selection, reports made by the departments throughout the consent decree and insight into a department’s compliance with the consent decree terms.

Term

Most recent consent decrees have lasted over a decade. The monitors have a financial disincentive to find agencies in compliance and new terms and conditions are continually being added to consent decree requirements. Agencies cannot achieve compliance when the goal posts keep moving and they cannot challenge the monitor’s findings.

Metrics for Measuring Success

DOJ uses cookie-cutter templates for consent decrees. Agencies must meet all the requirements in their consent decrees whether or not they are actually needed for reform and improvement. Almost all of the consent decree settlements that have taken place have used the same type of reforms, which include updating policies, trainings, and oversight. However, few settlements from the DOJ actually require the monitors or the jurisdictions to evaluate the impact of the required changes. Compliance with a consent decree is simply checking boxes rather than implementing meaningful reforms.

Even key supporters of consent decrees know they are far from perfect. In 2021, the DOJ held 50 listening sessions with key stakeholders, including current and former monitors, state and local officials, chiefs of police and law enforcement organizations, civil rights advocates, academics, and community leaders. The main takeaway was that key stakeholders agreed that the monitors are a problem — their selection process, oversight, high salaries, and lack of effectuating real change. However, no action has been taken to reform the issue.

Case Studies Consent Decrees in Action

Seattle, Washington

Background: The Seattle consent decree began in 2012 following a letter from the American Civil Liberties Union to the then Attorney General alleging excessive use of force.

- Time:

- 13 years

- Status:

- Terminated – September 2025

- Cost:

- >$200 million

Result: After over a decade, the City of Seattle requested the termination of its consent decree in July 2025, which took effect in September. While under its decree, Seattle’s monitors were scrutinized heavily and involved in a public-facing texting scandal – leading to questions around the purity of their intentions and financial motives. Today, Seattle has fewer officers per capita than most major U.S. cities, with Washington ranking 51st in police staffing behind all 50 states and D.C. During this time, Seattle also saw a clear rise in both violent and property crime.

View Graph Graph Source: King 5

Cleveland, Ohio

Background: From 2012–2014, Cleveland police had two high-profile officer-involved killings of unarmed civilians, which led to the filing of the city’s consent decree in 2015 that was intended to last five years.

- Time:

- 10+ years

- Status:

- Ongoing

- Cost:

- >$60 million

Result: The department has faced challenges implementing the 400+ paragraphs of the consent decree. Cleveland’s police staffing shortfall is more severe than the national average. The monitor recently resigned after multiple scandals and billing irregularities.

New Orleans, Louisiana

Background: A consent decree was enacted in New Orleans in 2013. At the time, it was the most detailed consent decree to date, and more than 300 officers left the department within the first two years. In 2019, the federal judge overseeing New Orleans’ consent decree stated they hoped the city could be in full compliance with the agreement in 2020.

- Time:

- 12 years

- Status:

- Terminated, November 2025

- Cost:

- ~$150 million

Result: New Orleans’ consent decree only recently was terminated in November of 2025, despite meeting most of the demands of the decree years prior and having filed a motion in 2022 and in May of 2025 to end it. According to a report from the Louisiana Legislative Auditor's office, between 2019 and 2023, the department lost 26.6% of its staff, bringing the total number of sworn officers to its lowest point since the 1940s. As a result, response times have tripled, from 51 minutes in 2019 to 146 minutes in 2023.

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Background: In November 2014, a consent decree was filed between the City of Albuquerque and the DOJ.

- Time:

- 10.5 years

- Status:

- Complete

- Cost:

- ~$40 million

Result: In May 2025, the Albuquerque consent decree was terminated following full compliance with the agreement. The City produced nearly 6,000 pages of oversight reports, implemented all required reforms, but still experienced a 44% increase in police killings. The person who seems to have benefited the most from the consent decree was their monitor — who earned over $12 million while overseeing the consent decree.

Graphs

Graph Source: NOPD Staffing Dashboard

Graph Source: King 5

Where We Go From Here

More than 99% of police departments have never been under a consent decree. This does not mean they have not faced challenges; rather, it means they were able to improve and correct problems on their own. The use of consent decrees should be limited to extreme cases in which departments refuse to improve or are incapable of improving independently. In these rare instances, consent decrees can play a role in helping troubled police departments. However, the process must be reformed to be effective.

The current implementation process is deeply flawed. Consent decrees are a bipartisan issue — both sides of the aisle advocate for constitutional policing, but the question remains: what is the best way to achieve it? We can all agree that the current consent decree implementation and process is not producing the results that anyone is asking for.

To help remedy this and create a more effective system, PORAC is advocating for both regulatory and legislative changes that would reform the process and allow consent decrees to be as effective and impactful as possible — for both jurisdictions and the communities they serve. These changes include:

Time Limitations on Investigations and Monitors

Requiring the Attorney General to complete investigations into allegations against a jurisdiction within one year of initiation, provided the law enforcement agency under review grants the DOJ full access to relevant records, documents, and personnel. The DOJ must be required to prove a “pattern or practice” of unconstitutional policing by a preponderance of the evidence, supported by facts and data to ensure investigations are grounded in demonstrable systemic issues. If a consent decree is agreed upon after an investigation, it must not extend beyond five years from the date of approval unless the DOJ proves ongoing constitutional violations in court.

Monitor Selection Process and Requirements

PORAC proposes requiring consent decree monitors to be selected based on objective criteria that prioritize law enforcement experience, expertise in criminal justice research methods and cost efficiency. All selected monitors should be held to strict conflict-of-interest policies, undergo regular performance evaluations and disclose all financial interests related to their work prior to their service. More specifically, PORAC calls for the following reforms:

- Monitors must spend at least 40% of their time performing their services physically in the jurisdiction subject to the consent decree.

- Require the Attorney General to institute a five-year term limit for monitors and prohibit monitors from serving more than one term in any jurisdiction. Prevent monitors from serving simultaneously in more than one jurisdiction.

- Remove monitors who demonstrate inefficiency, ineffectiveness, bias, or profit-driven motives, subject to a review process established by the Attorney General.

- Require monitors to issue an annual public report that addresses:

- Progress on the agency’s compliance

- Personnel and salary data for personnel assigned to the project

- Annual crime statistics for the jurisdiction subject to the consent decree

- Sworn staffing numbers for the law enforcement agency in the jurisdiction subject to the consent decree.

PORAC believes that implementing these changes to the consent decree process will allow us to move forward in a way that prioritizes public safety while fostering productive, meaningful reform. Without these changes, peace officers will be unable to do their jobs effectively, and the communities they serve will be less safe as a result. PORAC remains committed to driving this change forward and encourages collaboration among federal elected officials and community stakeholders to create a safer tomorrow for all.