Women in law enforcement continue to make the profession proud by handling hostile situations without excessive force, improving community–police relations and pushing law enforcement toward being a more diverse and united profession. In honor of National Women’s History Month this March, we are proud to shine a light on some of the women leaders who’ve worn the badge with honor and gone above and beyond to protect our communities.

by CINDY DE SILVA

Narcotics Prosecutor

Lining the walls of the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office (ACSO) Regional Training Center are photos of ACSO academy graduates from years past. Among the proud faces, shiny smiles and upright postures, one will find several photos of female law enforcement officers-to-be from the way-back years, in uniform, wearing perfectly pressed … skirts.

What a difference a few decades make.

In honor of National Women’s History Month, PORAC Law Enforcement News will look at three female officers with undercover (UC) experience and the many women they represent: Women who embrace challenge, who think outside the box, who solve crimes using their wits and interpersonal communication skills, and who lift up others while showing the way forward.

Sally Fairchild

(HIDTA, retired)

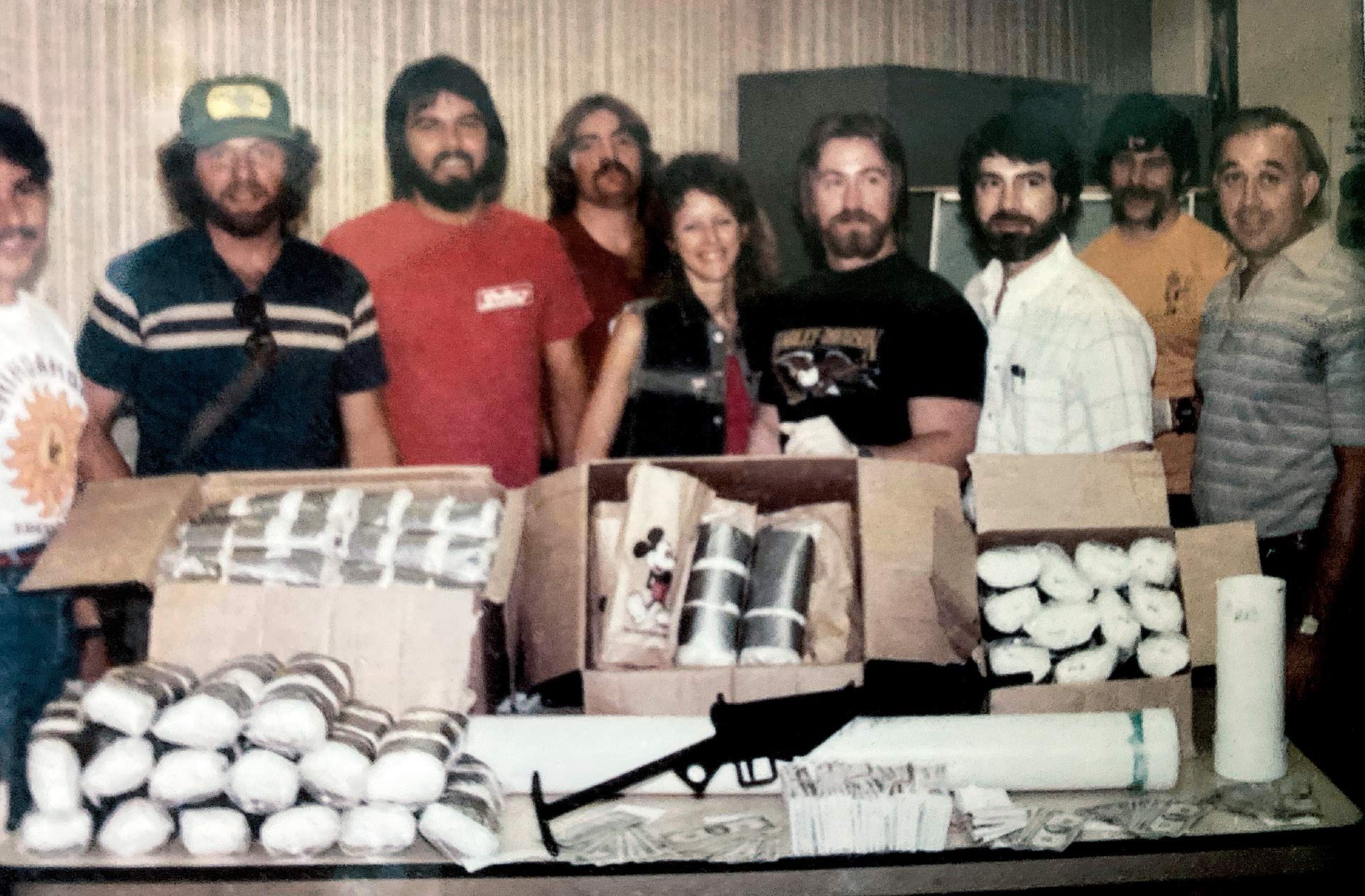

Meeting Sally in the general public, no one would ever peg her for a cop. Naturally warm, plain-speaking and engaging, she came of age in her UC career during the Miami Vice era, serving from 1981 to 2013. Her first role was as a reserve officer for the Hayward Police Department, then she served with the Fresno County Sheriff’s Office, including a stint on patrol before going to the Narcotics Unit, then she moved to the California Department of Justice-Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement. Finally, she retired as the deputy director of HIDTA in San Francisco.

“Fresno was a great time because that’s where I did most of my UC work,” she says. “Once you got to the state or the feds, you got further away from the street because you’re doing more pounds and kilos and organizations. I loved buying dope from the dope dealers. I used to say, ‘Pablo Escobar’s not gonna addict your kid — it’s going to be Charlie down the street.’ I would serve search warrants, and mothers would come out of their houses and clap because they knew who the dope dealers were. It’s the criminals in the neighborhoods who are destroying the neighborhoods.”

She began her UC career during her reserve time in Hayward, working an undercover gambling assignment in the card rooms. She got a job in a card room in order to work the gig. “I would never do that today, but back then, we just went in without cover,” she explains. “They were looking for violations of city ordinances. A lot of card clubs are basically loan sharks. A lot of stolen property comes through there, some dope, stuff like that. Gambling’s a horrible addiction. In Hayward at the time, there was an ordinance that if someone died at the card club, you had to stop playing for long enough to remove the body. Apparently, they needed an ordinance for that!”

To look the part for her UC narcotics assignment, she went to Kmart to “buy the same clothes the dopers bought. Back then, it was painter pants and long Pendletons — those are long-sleeved plaid shirts — because heroin addicts always wear long-sleeved shirts to hide their tracks. In Fresno, it’s hot — so if you’re wearing a long-sleeved shirt, you’re a doper. I had to buy them long enough so they would cover my gun,” she explains. “And that’s where I realized why they’d steal those clothes. They weren’t cheap!”

Her favorite informant was Shorty, who is long-since dead from drug use. “In my UC capacity, I bought heroin from Shorty and flipped him. And Shorty could buy heroin from anyone,” she proclaims with pride.

When asked to discuss a hairy situation she ever got in while undercover, she says, “One time, I was UC buying PCP. In those days, we went into houses, and I was buying PCP from a woman drug dealer, and apparently, they saw the surveillance group, so they all started screaming because the cops were around. Everyone started running, so I grabbed the dope I had paid for and left. When it’s all going to hell, if you just stay calm, you’ll be fine.”

On that note, she adds, “I rolled up to buy dope in a car once, a car buy. Sitting in the car next to the target was George, a pretty big dope dealer in Fresno. George knows me because I processed him two weeks before for 11550, and I’m UC here! George starts whispering to my target and says, ‘You’re a cop! Your name’s Sally Rivera!’ Which was my name back then due to my husband at the time. I looked at him and said, ‘Do I look like a Mexican?’ And the target goes, ‘Yeah, she’s not a cop.’ You gotta look at the psychology: He has already sold to me twice. He doesn’t want me to be a cop. So we did the sale, and he drove away. But that one tightened me up for a minute!”

While law enforcement is still a male-dominated field, Fairchild notes the advantages that females have in undercover roles. “I could go into any bar, and I won’t pose any threat to them. I could get an enormous amount of info. They may look at me as a victim but not as a threat, which makes you very valuable for UC work because you can go anywhere. So, as a woman, just do what you do best. Kicking down doors was not my strong point. But I can search females and protect males from female informants because they always cry to a male. They don’t cry to a female, and we won’t buy their story,” which makes females very valuable to their male counterparts, she says.

Fairchild also bravely called out some subversive gender dynamics sometimes at play. “With women,” she says, “I’ve found, in narcotics and any of those special units, it’s often only men — you’re the woman in the group. But when another female comes in, sometimes, they look at each other as competition because you’re no longer the special one. My support team was often the men.” On the flip side, she relates how she was driving with an officer once who stated his opinion that women don’t belong in law enforcement. “I wasn’t sure if he noticed I was female!” Fairchild jokes. “But he was a good cop and always backed me up. The way I feel, you have a right to your opinion —just as long as you treat me fairly.”

When asked her advice for women thinking of going into UC work, she says, “Narcotics? I loved doing it. The secret is, I would’ve done it for free. It’s like a bird dog that loves to hunt. If you love doing it, it’s great. If you don’t love it, it’s not really the job for you, because it’s demanding. Narcotics is like a very demanding mistress. It will demand everything from you that you’re willing to give it. Your family, your time, everything. So you just gotta know that and not give it what you don’t intend to give it.”

Faye Maloney

(Hayward Police Department)

Well known for her female empowerment efforts, 15-year police veteran Faye Maloney of the Hayward Police Department began as a dispatcher with the Sacramento Sheriff’s Office, then became a deputy for them, where she worked patrol and the jail. She lateraled to the Hayward Police Department, where she has worked patrol, vice, narcotics and her current role as a sergeant. Maloney was appointed by the board of supervisors to the Contra Costa Commission for Women and Girls and serves as its chair, and she is also active with the Women Leaders in Law Enforcement in the state of California and is a region chair for the California Narcotics Officers’ Association. She began her UC career in Sacramento when a school resource officer recruited her on a mission to do ecstasy buys in the high schools — but her true preparation for her life’s calling began long before, during her own school years.

At age 6, Maloney was parentally kidnapped by her father and taken abroad to various Middle Eastern and European countries, where she was sent to live with various relatives. “Life was filled with a lot of adversity,” she candidly admits, “and I was always taught and treated that I’m less than a man. This is why helping women in law enforcement and women in general is important to me; supporting women, empowering women — I lived the real aspects of the inequality of women.”

Fresh off a crisis negotiation call, Maloney calmly recounted how she used to ride a horse to school, but one day, when she was 14, instead of getting on her horse, she grabbed her passport, dressed herself fully so no one would know she was a child and took a taxi to the Jordanian Embassy to escape, where they facilitated her escape and returned her to the United States.

Maloney has developed and led various trainings, particularly for women in UC roles, and, like Fairchild, she addresses some uncomfortable realities to shine a light in the darkness. “Women need to be supportive of one another,” she says pointedly. “Women shouldn’t compare themselves to anyone but themselves. Jealousy should be checked at the door. At times, it can be masked as being overly competitive.”

Poignantly, Maloney observes, “I feel a lot of us become officers because of adversity we have experienced in our own lives. It’s so important to navigate all unaddressed trauma that made us want to serve our communities. The unaddressed trauma needs to be dealt with before we help others so we can understand our own triggers to protect our mental health. That’s so important.” She designed a mental wellness symposium during the pandemic years that addressed multiple causes of, and resources to help with, divorces, pill addictions, suicide prevention and more. “All this can be helped with mental wellness training,” she says.

Her time abroad as a child has given her keen insights into UC investigative work. “The first undercover class I put on focused on human trafficking,” she relates. “I began by discussing human trafficking all over the world and then narrowed it down to how the officers can understand and apply it to their own communities. If we don’t understand how other countries and their cultures function in their territories, how can we understand how things function in their communities here that fall victim to human trafficking? America is the melting pot of the world — we have a community that represents every part of the world, which is what makes our country beautiful for its diversity. Understanding other cultures is so vital to doing this job well and being able to navigate and break barriers.”

Her UC work in narcotics, in particular, had her buying meth, working with informants, doing money flashes and the like. When asked about some funny stories or advice for women considering a UC role, she responded with a laugh, “Make sure your informants don’t go buy McDonald’s with the money you give them to buy drugs.” She then laughed even more before admitting, “There’s a lot of funny stories. This definitely was the best job I had.”

Maloney continues, “It’s the best job you can have because it gives you the ability to learn how to navigate the gray area, especially with people who want to give you information but they don’t want to be identified. Like later, if you’re in a homicide unit, your past experiences will help you with getting the Hobbs order or not disclosing the informant and more exposures with in-camera hearings,” she observes. “And the networking in narcotics is phenomenal. You will make lifelong friends and relationships with so many people across the state, nationally and, sometimes, internationally — not just because of the training you attend but also because your investigations are tied to so many different states and countries.”

She urges women who aren’t sure about an assignment like this to “Go ask someone! A lot of women say they want to go into SWAT, but they don’t. Is it because it’s intimidating? Is the environment welcoming? Take a chance on yourself and your career. We have so many pioneers. I want to find what women are afraid of and put it in front of them to challenge them. I want to inspire them to do what they think they can’t,” she says.

“In general, women in law enforcement need to give themselves more credit, believe in themselves more and stop caring about what others think,” she encourages.

A mentor of Maloney’s said to her once, “If you think you can or can’t do it, you’re right.”

Adrianna Afanasiev

(Stockton Police Department)

An officer for over 11 years, Stockton Police Department Detective Adrianna Afanasiev began as a reserve officer on patrol for the San Jose Police Department during a budget crunch when Stockton offered her a full-time position. Starting on patrol, she later joined the proactive street team, moved to Robbery/Homicide, and is now in the Gang Unit.

With no formal training at the time in the art of UC work, she was asked to participate in occasional prostitution missions on “the blade” (in Stockton, Wilson Way) while on patrol, and later, on the proactive team and in detectives. “Going in, I had just the bare-minimum knowledge of these cases — I didn’t know what the prices were or any of the slang terminology. Vice gave me a brief run down, and then I started role playing once I hit the streets. Talking plays a huge role in this,” she says.

Afanasiev adds, “I learned real quick that you should stick with something you’re knowledgeable about and not try to be something you’re not and overthink it. I tried at first to come off as very promiscuous. After working my first mission and getting more comfortable, I fell into my own niche on the way I wanted to talk to people. I toned down the promiscuity thing.”

Her initial mistake, she reflects, was trying too hard, and she advises females new to UC work to not try to overcompensate due to being scared when trying something new.

When asked about safety measures, Afanasiev mentioned she would never get into one of the john’s cars; instead, she and the john would agree to terms, she’d point to a place for him to drive and meet her, and then an officer would pull him over. She illustrated the reason for such caution by telling an anecdote of the time her fellow UC female partner, Yanell Mauldin, had walked up to a car. The driver, whom they presume to have been a pimp, began yelling at her to get inside the car. He was reaching for what she thought to be a weapon. Mauldin was able to get the attention of a marked police unit which, not assigned to their mission, happened to be only two cars behind the pimp, and gave chase and caught the suspect. Afanasiev relates, “And me being me and always on my toes, I’m always looking on the inside of the car as I talk to them from the outside, looking for weapons.”

On that subject, she says, “We would always carry our purses with our guns, but they’re not as accessible to get to. So, instead of us reaching for our weapons, we’d have a hand sign for help and try to defuse the situation with the subject while waiting for help to arrive.”

As for what women can bring to the UC role, she remarks, “When men do UC stuff, criminals are more likely to think that they’re cops versus women. We are a book of excuses. I could go buy drugs, and if they want me to use, I can say I’m pregnant, or my man won’t let me or whatever. We, as women, get overlooked — there are so many more roles that we can play than men. And we can change our appearances a lot more than men can.”

On appearances, she adds with a smile, “One time, I was working graves and got called to a burglary on Wilson Way. The reporting party told me he recognized me from around there and not as a police officer.”

When asked if she would recommend UC work to other female officers, Afanasiev says unhesitatingly, “Oh, I would tell them to do it 100%. It’s a great experience — not only do you learn to get out of your element and into character, but you learn from the people you’re talking to. I’d actually talk to the prostitutes, how much they’d charge, how they got into the lifestyle, where they were from, and they would tell me. You’re kind of dipping your toes into the human trafficking world, and conversing with them helped me later on in my proactive policing role to talk to the human trafficking victims. It all ties together. Lots of pimps are associated with gangs, and gangs are associated with guns and drugs. It all goes hand in hand.”

She adds, “Once I got a taste of human trafficking, I was all about it. It’s a huge problem, and we don’t have enough law enforcement resources to combat it. After interviewing a particular HT victim, I knew that was exactly what I wanted to do. I still want to do that. If we ever had a specific HT unit dedicated to rescuing girls, I’d want to lead it. I am all in.”

About the Author

Cindy De Silva of the San Joaquin County District Attorney’s Office has been a prosecutor for 22 years. She is the 2022 California Narcotic Officers’ Association Prosecutor of the Year, the 2016 California District Attorneys Association Instructor of the Year and the 2009 Stockton Crime Stopper of the Year.