Dan Minjares

Volunteer Chaplain

Cochise County Sheriff’s Office

Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part article exploring the issue of cumulative career stress in the law enforcement profession. Part 1 appeared in the June 2023 issue of PORAC Law Enforcement News.

The challenges, issues and scenes that deputies have to witness, along with the emotions they have to control, make their emotional rucksack heavier with each shift. As the rocks increase, the negative consequences of an ever-heavier emotional rucksack can start to surface in three areas. One area it impacts is at work. A too-heavy emotional rucksack can lead to decreased job performance and effectiveness, lowered job satisfaction, indifference, lack of patience, excessive force issues and citizen complaints. Another is in physical problems. These can include anxiety, depression, sleep problems, increased alcohol use and thoughts of suicide. The last area is in problems in marriage and family relationships; deputies become more easily angered, withdrawn, have mood swings and are hypervigilant.

For major traumatic events, most law enforcement agencies have procedures, such as critical incident stress management (CISM), critical incident stress debriefings (CISD) or similar methods to address and assist those who were involved at the scene. Yet the day-to-day routine calls that aren’t considered to need this level of specific attention go unaddressed and continue to add to the deputy’s emotional rucksack.

So what can be done for this significant, easily ignored or dismissed issue? It isn’t what one deputy told me, “When your rucksack gets full, you just get a bigger one.”

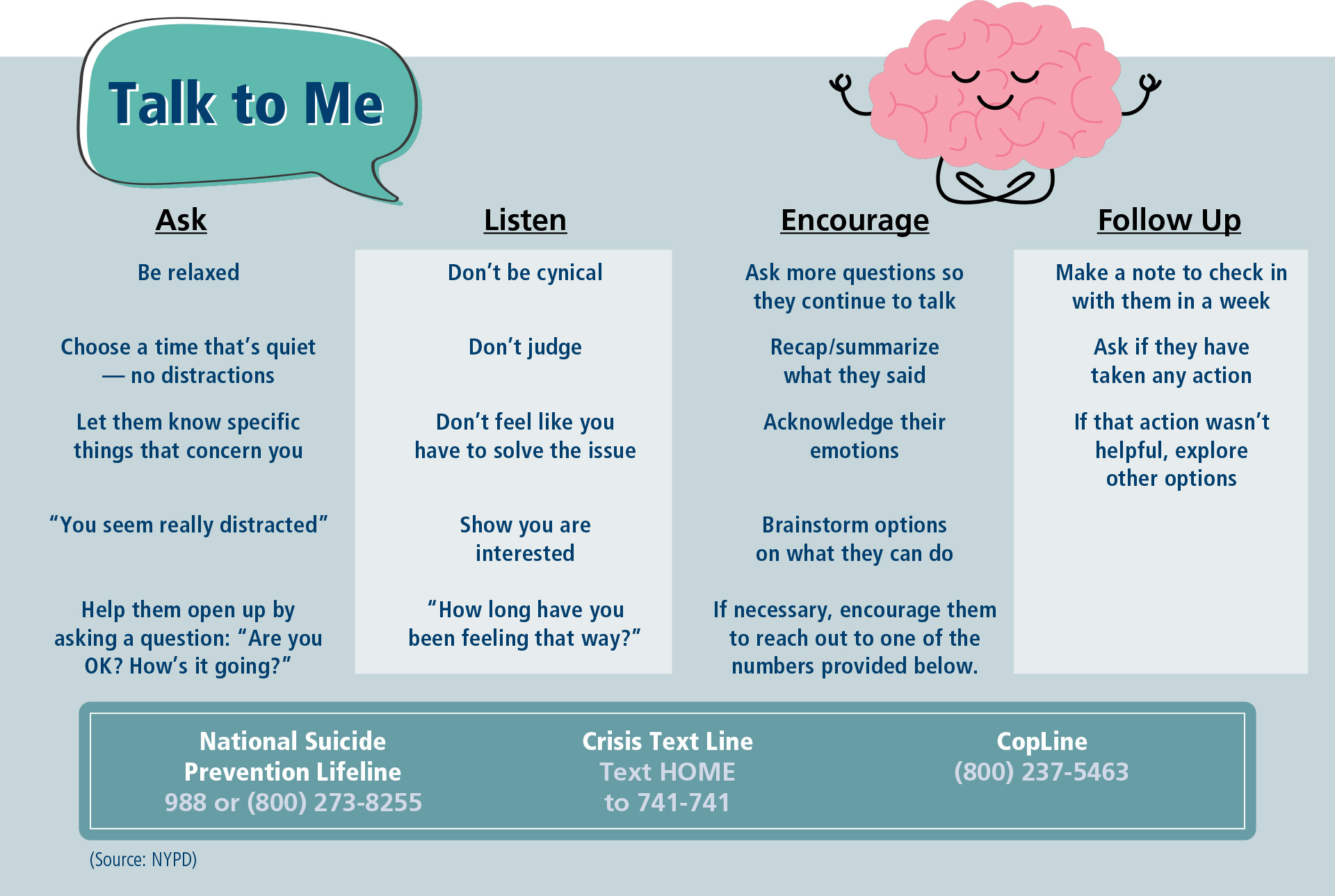

The FOP/NBC study of 8,000 active and retired sworn officers found that 73% of respondents indicated that peer support, talking to another deputy, was the most effective way to work through the stresses they face on the job. What makes this finding even more significant is that 65.4% of the officers in the study had from 16 to 25 years of on-the-job experience. While deputies have a wide variety of skills, abilities and talents, they probably don’t consider themselves to be counselors. As a result, they may be hesitant to talk to another deputy about the stress of the job. As an Army chaplain, I learned that while I could ask a soldier how they were doing, it was easy for them to hide or disguise what was happening in their lives and tell me they were fine. To other soldiers, their friends who knew them better, hiding their difficulties and thoughts was much harder. The same is true for deputies. Through spending time together during answered calls, getting coffee or a meal, they come to know each other. This puts them in a good position to know when something is just not quite right. Reaching out to another deputy can seem intimidating, risky and uncomfortable, but it can provide a way for them to talk about the challenging feelings, thoughts and emotions caused by the stressors of the job. Talking can help them put into words what is going on inside. It takes courage to reach out and talk to another deputy who may seem to be struggling, but it is important. A guide from the New York Police Department entitled “Talk to Me” provides a way for deputies to reach out to one another to help in talking about their emotional rucksack.

Deputies’ vehicles are required to have regular services and maintenance to keep them performing at their peak level capabilities and extend their longevity. It is even more important for a deputy to perform regular services and maintenance on their emotional rucksack. As they do this important maintenance, they will continue to serve at peak effectiveness and avoid the negative consequence of a too-heavy emotional rucksack.

In my 26 years as an Army chaplain, I have talked to countless soldiers, spouses and family members about the problems and issues in their lives. In these conversations, I discovered that talking does help. I don’t understand how or why, I just know that, in fact, it does.

Cumulative career stress is carried by every deputy in an emotional rucksack and is a reality of a career in law enforcement. That rucksack does provide positive benefits and negative consequences, and it reflects the rewards and challenges of caring for the people of the counties and cities they serve. Professional basketball player Kevin Love, who struggled for many years with thoughts of suicide, said, “Nothing haunts us like the things we don’t say, so me keeping it in is actually more harmful.” For deputies, not keeping it in is having the courage to talk and lighten the weight of their emotional rucksack. It can seem to be a daunting task to reach out to someone or be willing to talk, but ultimately do it for yourself, do it for your family and do it for the agency you work for.

About the Author

Dan Minjares, B.A., M.S., M.Div., served as a U.S. Army chaplain for 26 years and was previously licensed in the state of Kansas as a clinical marriage and family therapist. He has been a volunteer with the Sheriff’s Assist Team for the Cochise County, Arizona, Sheriff’s Office for six years, and for four years has provided volunteer chaplain support for the deputies of the CCSO.

References

“When Stress Builds Up: Strategies to Overcome Cumulative Stress and Burnout, Guidance for Agency Leaders.” International Association of Chiefs of Police. tinyurl.com/29jeff8k.

“Feeling Scorched: Burnout, Traumatic Stress and the Need for Self-Care.” International Association of Fire Fighters Center of Excellence for Behavioral Health Treatment and Recovery. 30 October 2017, tinyurl.com/snekwt7s.

Queirós, Cristina et al. “Job Stress, Burnout and Coping in Police Officers: Relationships and Psychometric Properties of the Organizational Police Stress Questionnaire.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Vol. 17,18 6718. 15 September 2020, tinyurl.com/yc2tv6az.

Mumford, Elizabeth et al. “Law Enforcement Officers Safety and Wellness: A Multi-Level Study.” National Institute of Justice. 23 April 2020, tinyurl.com/yvxej59m.

Report on FOP/NBC Survey of Police Officer Mental and Behavioral Health, 2018.

“Cumulative PTSD — a Silent Killer.” Badge of Life USA. 2014, tinyurl.com/dfu595he.

“Coming to Terms With Cumulative Trauma.” International Association of Fire Fighters Center of Excellence for Behavioral Health Treatment and Recovery. 12 November 2019, tinyurl.com/2p8bkau2.

Beshears, Michelle. “Police Officers Face Cumulative PTSD.” Police1. 3 April 2017, tinyurl.com/3suasajs.

Kirschman, Ellen. “Treating Traumatic Stress in First Responders.” Psychology Today. 8 February 2023, tinyurl.com/bdrc92yk.